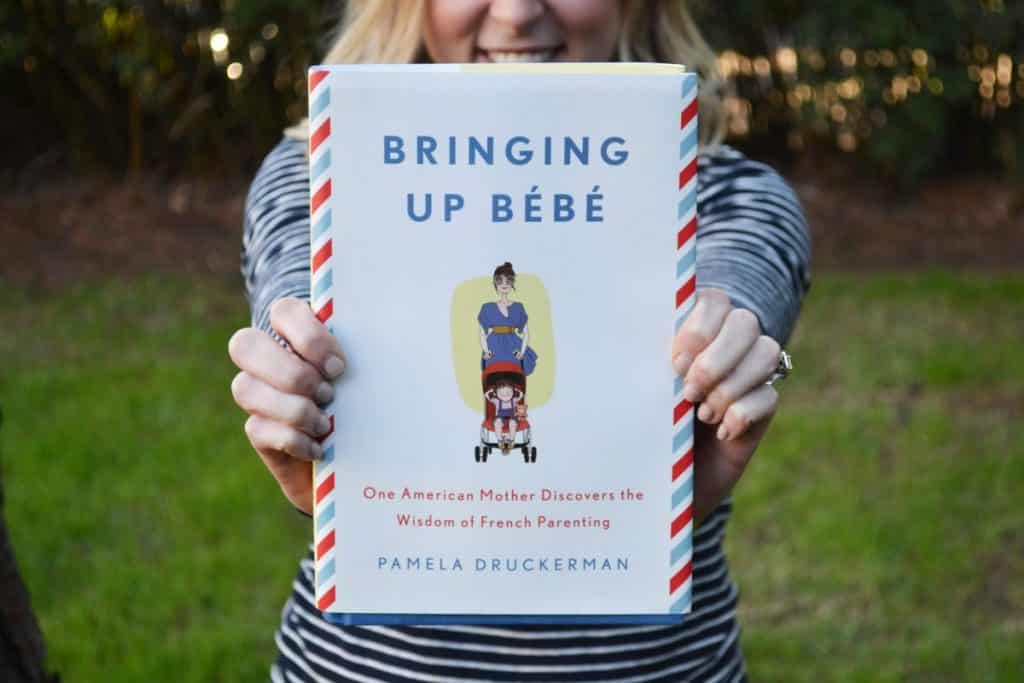

This New York Times Bestseller has had a lot of parents talking over the years. Can it really deliver on its promise to guide you to raise bright, well-mannered children while maintaining a fulfilling adult life? We’ve read the book and had a Book Club Live on Facebook discussing it. Watch the video below after Nina’s notes to learn more. If you’d like to read the book Bringing Up Bébé (buy it here) but don’t have the time to, read Nina’s Notes below to get the full scoop on each chapter. 🙂

Nina’s Notes: Bringing Up Bébé

At the beginning of the book, Pamela Druckerman (the author) gives us a glossary of French parenting terms. After reading a few of them, I was curious to open the next few pages and see what it was all about. My favorite ones were:

- autonomie (oh-toh-no-mee)—autonomy. The blend of independence and self-reliance that French parents encourage in their children from an early age.

- complicité (kohm-plee-see-tay)—complicity. The mutual understanding that French parents and caregivers try to develop with children begining from birth. Complicité implies that even small babies are rational beings with whom adults can have reciprocal, respectful relationships.

- équilibre (eh-key-lee-bruh)—balance. Not letting any one part of life—including being a parent—overwhelm the other parts.

- sage (sah-je)—wise and calm. This describes a child in control of themselves or absorbed in an activity. Instead of saying, “Be good,” French parents say, “Be sage.”

“French Children Don’t Throw Food”

In her introduction, Pamela Druckerman is at a French restaurant with her 18-month-old daughter, who is running around making a mess and lots of noise. She looked around and noticed the other French children were “sitting contentedly in their high chairs, waiting for their food, or eating fish and even vegetables. There’s no shrieking or whining, and everyone is having one course at a time. And there’s no debris around their tables.” She wondered, “Are French kids just genetically calmer than ours?” This set her on an exploration of French parenting. After years of investigative work, she thinks she’s discovered what French parents are doing differently. She finds out that to be a different kind of parent, you don’t just need a different parenting philosophy. You need a very different view of what a child actually is.

Chapter 1: “Are You Waiting for a Child?”

- After leaving New York City, Pamela moves to Paris to live with her boyfriend. They soon get married and conceive, and Pamela begins to notice the difference between American and French ways of parenting.

- Americans are neurotic about pregnant people. The Parisians are not. The French will light a cigarette beside you and ask, “Are you waiting for a child?” Which means “Are you pregnant?” in French.

Chapter 2: “Paris Is Burping”

- Frenchwomen don’t treat pregnancy like an independent research project. While French parenting resources are abundant, they aren’t required reading.

- One Parisian mother tells Pamela, “I don’t think you can raise a child while reading a book. You have to go with your feeling.”

- American women typically demonstrate commitment by worrying and showing how much they’re willing to sacrifice, even while pregnant. Frenchwomen signal their commitment by projecting calm and flaunting that they haven’t renounced pleasure.

- The French are calmer about sex. They are calmer about food. The point in France isn’t that anything goes. Instead, it’s that women should be calm and sensible.

- The main reason pregnant Frenchwomen don’t get fat is that they are careful not to overeat. Frenchwomen don’t see pregnancy as a free pass to overeat because they haven’t denied themselves the foods they love (or secretly binging on those foods) for most of their adult lives. Instead, they are very mindful of what they eat.

- Despite being the birthplace of Dr. Fernand Lamaze, epidurals are now extremely common in France.

- In France, the way you give birth doesn’t situate you within a value system or define the sort of parent you’ll be. It is, for the most part, a way of “getting your baby safely from your uterus into your arms.”

- Each newborn is issued a white softcover book called a carnet de santé, which will follow the child through the age of eighteen. Doctors record every checkup and vaccination in this book and plot the child’s height, weight, and head size. It also has commonsense basics on what to feed babies, how to bathe them, when to go for checkups, and how to spot medical problems.

Chapter 3: “Doing Her Nights”

- Pamela is confused by the question, “Is she doing her nights?”

- The French use this expression to mean sleeping through the night

- It is usual for French babies to sleep through the night at six weeks or eight weeks old. The French expect their babies to sleep through the night between three and six months old.

- The French keep their babies in the sunlight during the day and put them to bed in the dark at night.

- Almost all French parents can articulate how they observe their babies, following the rhythms they observe. “French parents talk so much about rhythm that you’d think they were starting rock bands, not raising kids.”

- While speaking with a French pediatrician living in New York, Pamela learns the secret of “The Pause.”

- “Give your baby a chance to self-soothe, don’t automatically respond, even from birth.” This pause is crucial. “The parents who were a little less responsive to late-night fussing always had good sleepers, while the jumpy folks had kids who would wake up repeatedly at night until it became unbearable.” And whether they are breastfed or bottle-fed doesn’t matter.

- Young babies move and make noise while they’re sleeping. This is normal, and if parents rush in and pick the baby up every time he makes a peep, they’ll sometimes wake him up.

- Babies wake up between their sleep cycles, which last about two hours. It’s normal for them to cry a bit when they’re first learning to connect these cycles. Suppose a parent automatically interprets this cry as a demand for food or a sign of distress and rushes in to soothe the baby. In that case, the baby will have difficulty learning to connect the cycles on his own. That is, he’ll need an adult to come in and soothe him back to sleep at the end of each cycle.

- The pause doesn’t have the brutal feeling of sleep training. It’s more like sleep teaching. But the window is pretty small, only until around four months.

- Another reason for The Pause is “to teach them patience.”

- French parents believe it’s their job to gently teach babies how to sleep well, the same way they’ll later teach them to have good hygiene, eat balanced meals, and ride a bike.

- A meta-study of dozens of peer-reviewed sleep papers concludes that what’s critical is something called “Parent education/prevention.” This involves teaching pregnant women and parents of newborns about the science of sleep and giving them a few basic sleep rules. Parents are supposed to start following these rules from birth to when their babies are just a few weeks old. What are the rules?

- The authors of the meta-study point to a paper that tracked pregnant women who planned to breastfeed. Researchers gave some of the women a two-page handout with instructions. One rule on the handout was that parents should not hold, rock, or nurse a baby to sleep in the evenings to help him learn the difference between day and night. Another instruction for week-old babies was that if they cried between midnight and five a.m., parents should re-swaddle, pat, rediaper, or walk the baby around. The mother should offer the breast only if the baby continues crying after that.

- Additional instruction was that, from the child’s birth, the mothers should distinguish between when their babies were crying and when they were just whimpering in their sleep. In other words, the mother should pause before picking up a noisy baby to ensure he’s awake.

- The researchers explained the scientific basis for these instructions. A “control group” of breastfeeding mothers had gotten no instruction. The results were remarkable: Babies in the treatment and control groups had nearly identical sleep patterns from birth to three weeks old. But at four weeks old, 38% of the treatment-group babies were sleeping through the night versus 7% of the control group babies. All the treatment babies were sleeping through the night at eight weeks, compared with 23% of the control babies. The authors’ conclusion is resounding: “The results of this study show that breastfeeding need not be associated with night waking.”

- The researchers say that if you miss the fourth-month window, they believe in cry it out.

- To the common worry that a four-month-old is hungry at night: “She is hungry. But she does not need to eat. You’re hungry in the middle of the night, too; it’s just that you learn not to eat because it’s good for your belly to take a rest. Well, it’s good for hers, too.”

Chapter 4: “Wait!”

- French babies all eat at roughly the same time. With slight variations, mothers tell Pamela that their babies eat at about 8 am, 12 pm, 4 pm, and 8 pm. In other words, by about four months old, French babies are already on the same eating schedule they’ll be on for the rest of their lives (grown-ups usually ditch the 4 pm snack).

- The French seem to collectively have achieved the miracle of getting babies and toddlers not just to wait but to do so happily.

- Walter Mischel is the world’s expert on how children delay gratification. He is famous for devising the “marshmallow test” in the late 1960s, testing children’s ability to wait and delaying gratification.

- In the mid-1980s, Mischel revisited the kids from the original experiment to see if there was a difference between how good and bad delayers were faring as teenagers. The longer the children had resisted eating the marshmallow as four-year-olds, the higher Mischel and his colleagues assessed later on. Among other skills, the good delayers were better at concentrating and reasoning. They “do not tend to go to pieces under stress.”

- Could it be that making children delay gratification—as middle-class French parents do—makes them calmer and more resilient? Whereas middle-class American kids, who are generally more used to getting what they want right away, fall apart under stress?

- Instead of saying “quiet” or “stop” to rowdy kids, French parents often just issue a sharp attend, which means “wait.”

- French parents don’t expect their kids to be mute, joyless, and compliant. Parents just don’t see how their kids can enjoy themselves if they can’t control themselves.

- Having the willpower to wait isn’t about being stoic. It’s about learning techniques that make waiting less frustrating. “There are many many ways of doing that, of which the most direct and the simplest . . . is to self-distract,” Mischel says.

- Parents don’t have to specifically teach their kids “distraction strategies.” Kids learn this skill independently if parents allow them to practice waiting.

- French parents don’t worry that they will damage their kids by frustrating them. On the contrary, they think their kids will be managed if they can’t cope with frustration. They also treat dealing with frustration as a core life skill. Their kids simply have to learn it.

- The French believe that even babies are rational people who can learn things.

- Caroline Thompson, a family psychologist, says we shouldn’t mistake angering a child for bad parenting.

- French principles:

- The first is that a baby should eat at roughly the same times each day after the first few months.

- The second is that babies should have a few big feeds rather than a lot of small ones.

- And the third is that the baby should fit into the rhythm of the family.

Chapter 5: “Tiny Little Humans”

- American parents think that the better we are at parenting, the faster our kids will develop. French parents don’t seem so anxious for their kids to get a head start. They don’t push them to reach milestones ahead of schedule.

- “Awakening” is about introducing a child to sensory experiences, including tastes. It doesn’t always require the parent’s active involvement. It can come from observation and play as the child’s senses are sharpened. It’s the first step toward teaching him to be a cultivated adult who knows how to enjoy himself. Awakening is a kind of training for children to learn how to soak up the pleasure and richness of the moment.

- Dolt thought that parents should listen carefully to their kids and explain the world to them. But she thought that this world would include many limits and that the child, being rational, could absorb and handle these limits.

- The parents I see in Paris today seem to have found a balance between listening to their kids and being clear that the parents are in charge (even if they sometimes have to remind themselves of this).

Chapter 6: “Daycare?”

- American parents tend to voice daycare if they can afford to by hiring nannies, staying at home, or utilizing family connections. But upper-middle-class parents are fighting to get their children into public, neighborhood daycares or “crèche.”

- French mothers are convinced that the crèche is good for their kids. In Paris, about a third of kids under the age of three go to the crèche, and half are in some kind of collective care. They think kids are safer in settings with many trained adults looking after them rather than being “alone with a stranger” (like a nanny).

- An in-house cook at each crèche prepares a four-course lunch from scratch each day. A truck arrives several times weekly with seasonal, fresh, and sometimes even organic ingredients.

- In France, working in daycare is a very competitive career.

Chapter 7: “Bébé AU Lait”

- Long-term breastfeeding is very rare in France, and almost everyone abandons it shortly after leaving the hospital.

- Some locals report that breastfeeding still has a peasant image, from the days when babies were farmed out to rural wet nurses. Others say that artificial milk companies pay off hospitals, give free samples in maternity wards, and advertise mercilessly.

- Pierre Bitoun, a French pediatrician and longtime proponent of breastfeeding in France, says many Frenchwomen think they don’t have enough milk. Dr. Bitoun says the real problem is that French maternity hospitals often don’t encourage mothers to feed their newborns every few hours. That’s critical in the beginning to stimulate mothers to produce enough milk. Otherwise, a recourse to formula starts to seem inevitable.

- Even though French children consume enormous amounts of formula, they beat American kids on nearly all health measures. France ranks about six points above the developed-country average in UNICEF’s overall health-and-safety ranking, including infant mortality, immunization rates until age two, and deaths from accidents and injury up to age nineteen. The United States ranks about eighteen points below the average.

- In Paris, three months seems to be the magic number for regaining the pre-baby body.

- There is an assumption that even good mothers aren’t at the constant service of their children and that there’s no reason to feel bad about that.

- French women don’t just permit themselves physical time off; they also mentally detach from their kids. The dominant social message in France is that while being a parent is very important, it shouldn’t subsume one’s other roles. Mothers shouldn’t become “enslaved” to their children.

- American women think of their identities as “mom” and “woman” as very separate—Mom clothes vs. sexy clothes. In France, these roles are fused, and you can see them at any time.

Chapter 8: “The Perfect Mother Doesn’t Exist”

- In a 2010 survey by the Pew Research Center, 91% of French adults said the most satisfying kind of marriage is one in which both husband and wife have jobs. (Just 71% of Americans and Britons said this.)

- For American mothers, guilt is an emotional tax we pay for not being perfect.

- The French consider guilt unhealthy and unpleasant and try to banish it. “Guilt is a trap,” says Pamela’s friend Sharon, a literary agent. When she and her Francophone girlfriends meet for drinks, they remind one another that “the perfect mother doesn’t exist . . . we say this to reassure each other.”

- The Perfect Mother Is You

- Frenchwomen have a conviction that it’s unhealthy for mothers and children to spend all their time together. They believe there’s a risk of smothering kids with attention and anxiety or developing a situation where a mother’s and a child’s needs are too intertwined.

- When Americans talk about work-life balance, we’re describing a kind of juggling, where we’re trying to keep all parts of our lives in motion without screwing up any of them too badly. The French also talk about l’equilibre. But they mean it differently. For them, it’s about not letting any one part of life–including parenting–overwhelm the rest.

Chapter 9: “Caca Boudin”

- Caca boudin means “poop sausage.” Their three-year-old uses it to mean “whatever,” “leave me alone,” and “none of your business.” It’s an all-purpose retort.

- Learning to read isn’t part of the French curriculum until the equivalent of first grade, the year that kids turn seven. They believe that before age seven, it is much more important for children to learn social skills, organize their thoughts, and speak well.

- While reading isn’t taught, speaking is. It turns out that the primary goal of maternelle (French preschool) is for kids of all backgrounds to perfect their spoken French.

- French logic is that if children can speak clearly, they can also think clearly.

- A French child learns to “observe, ask questions, and make his interrogations increasingly rational. He learns to adopt a point of view other than his own, and this confrontation with logical thinking gives him a taste of reasoning. He becomes capable of counting, of classifying, ordering, and describing . . . “

- It’s very important in France to say s’il vous plait (please), merci (thank you), bonjour, (hello), and au revoir (good-bye). Saying bonjour is important to the French because it acknowledges the other person’s humanity. Children must do the same.

- This helps kids learn they’re not the only ones with feelings and needs.

- Pamela finally decides to ask some French adults about this mysterious word, “caca boudin.” It turns out that it is a curse word, but one that’s just for little kids. They pick it up from one another around the time they start learning to use the toilet. The adults I speak to recognize that since children have so many rules and limits, they need some freedom, too. The word gives kids power and autonomy.

Chapter 10: “Double Entendre”

- Pamela talks about her desire for a second child and how it is much harder to get pregnant this time. She is taking meds and seeing an acupuncturist; nothing is working. Then, after taking a shot of medicine and a night of love in Brussels, she becomes pregnant. With twins! Twin boys. 🙂

- She has a vaginal birth and discovers how difficult life becomes with three children under three. She begins to doubt everything, such as if she named the boys the correct names and if she’s had too many children. But there are also moments of delight when things are good.

Chapter 11: “I Adore This Baguette”

- Research shows marital satisfaction has fallen, and mothers find it more pleasant to do housework than take care of their kids. American social scientists now pretty much take for granted that today’s parents are less happy than non-parents. Studies show that parents have higher rates of depression and that their unhappiness increases with each additional child.

- In France, they are much more concerned about a woman’s pelvic floor after childbirth. Pam describes her “perineal reeducation” visits with her reeducator, Monica, a slim Spanish woman. She was prescribed by her doctor ten reeducation visits.

- Sacrificing your sex life for your kids is considered wildly unhealthy and out of balance.

- The couple is the most important. It’s the only thing that you choose in your life. Your children, you didn’t choose. You chose your husband. So, you’re going to make your life with him. So you have an interest in it going well. Especially when the children leave, you want to get along with him.

- There are structural reasons why Frenchwomen seem calmer than American women. They take about twenty-one more vacation days each year. France has less feminist rhetoric but many more institutions enabling women to work. There’s the national paid maternity leave (the United States has none), the subsidized nannies and crèches, the free universal preschool from age three, and a myriad of tax credits and payments for having kids. All this doesn’t ensure that there’s equality between men and women. But it does ensure that Frenchwomen can have both a career and kids.

- Pamela tells how her friend, Helene, said a very simple, sweet, and honest thing to her husband. He also picked up a crusty baguette when he went to the store to pick up a few things. Helene exclaims, “J’adore cette baguette!” (I adore this baguette!) to her husband, William. Pam can’t imagine saying anything like that to Simon. She usually would say that he’d bought the wrong baguette or worry that he’d left a mess that she’d have to clean up. That sheer girlish pleasure sadly doesn’t exist between them anymore. She tells Simon this baguette story, and he says, “We need that j’adore settee baguette,” and she agrees that they absolutely do.

Chapter 12: “You Just Have to Taste It”

- Dominique, a French mother who lives in New York, says at first she was shocked to learn that her daughter’s preschool feeds the kids every hour all day long. She was also surprised to see parents giving their kids snacks throughout the day at the playground. “If a toddler starts having a tantrum, they will give food to calm him down. They use food to distract them from whatever crisis,” she says.

- French kids are so used to fresh food that processed food tastes strange to them. There aren’t very many “kid’s menus” in France. At most restaurants, children are expected to order from the regular menu.

- French kids eat only at mealtimes and afternoon gouter (snack).

- The French government’s campaign reminding people to eat at least “five fruits and vegetables per day” has become a national catchphrase.

- No French children will eat just one type of food; their parents will simply not allow this. Of course, they like certain foods more than others. And there are plenty of finicky French three-year-olds. But these children don’t get to exclude whole categories of textures, colors, and nutrients just because they want to. The extreme pickiness that’s come to seem normal in America and Britain looks to French parents like a dangerous eating disorder or, at best, a wildly bad habit.

- Just 3.1% of French five- and six-year-olds are obese. In America, 10.4% of kids between two and five are obese.1 This gap is much wider for older French and American kids.

- French parents don’t start their babies off on rice cereal. From the first bite, they serve babies flavor-packed vegetables. The first foods that French babes typically eat are steamed and pureed green beans, spinach, carrots, peeled zucchini, and the white part of leeks.

- Parents see it as their job to teach their children to appreciate fruits and vegetables. They believe that just as they must teach the child how to sleep, wait, and say bonjour, they must teach her how to eat.

- “There’s no such thing as ‘kids’ food.'”

- For a French kid, candy has its place. It’s a regular enough part of their lives that they don’t gorge on it like freed prisoners the moment they get their hands on it. Mostly, children seem to eat it at birthday parties, school events, and as the occasional treat. On these occasions, they’re usually free to eat all they want. Kids, too, need moments when the regular rules don’t apply. But parents decide when these moments are.

- French parents aren’t afraid of sugary foods. They will generally serve cake or cookies at lunch or the gouter. But they don’t give kids chocolate or rich desserts with dinner. “What you eat in the evening just stays with you for years,” Pamela’s friend Fanny explains.

- At lunch and dinner, they serve vegetables first when the kids are the hungriest.

Chapter 13: “It’s Me Who Decides”

- Many French parents have an easy, calm authority with their children, and their kids actually listen to them. French children aren’t constantly dashing off, talking back, or engaging in prolonged negotiations. But how exactly do French parents pull this off?

- Pamela reflects, “The French way sometimes is too harsh. They could be a little more gentle and friendly with kids, I think. But I think the American way takes it way to the extreme, of raising kids as if they are ruling the world.”

- “We have a saying in French: it’s easier to loosen the screw than to tighten the screw, meaning that you have to be very tough. If you’re too tough, you loosen. But if you’re too lenient… afterward to tighten, forget about it.”

- The kids need to understand that they’re not the center of attention and that the world doesn’t revolve around them.

- French parents often invoke the language of rights in defining limits for kids. Rather than saying, “Don’t hit Jules,” they say, “You don’t have the right to hit Jules.” This is more than a semantic difference. It feels different to say it this way.

- Another phrase that adults often use with children is “I don’t agree,” as in, “I don’t agree with you pitching your peas on the floor.” Parents say this in a serious tone while looking directly at the child. It establishes the adult as another mind that the child must consider. And it credits the child with having their own view about the peas, even if this view is being overruled.

- The more spoiled a child is, the more unhappy he is.

- Madeleine says that she’s not just trying to frighten children into submission. She says “the big eyes” work best when she has a strong connection with the child and mutual respect. She says the most satisfying part of her job is developing “complicity” with a child as if they see the world the same way and when she almost knows what the child is about to do before he does it.

- You must listen to the child, but it’s up to you to fix the limits.

- French parents mean something different than American parents when they call themselves “Strict.” Instead, they mean they’re very strict about a few things and pretty relaxed about everything else. That’s the cadre model: a firm frame surrounding a lot of freedom.

- “We should leave the child as free as possible, without imposing useless rules on him,” Francoise Dolto says in The Major Stages of Childhood. “We should leave him only the cadre of rules that are essential for his security. And he’ll understand from experience when he tries to transgress, that they are essential and that we don’t do anything just to bother him.” In other words, being strict about a few key things makes parents seem more reasonable and thus amens it more likely that children will obey.

Chapter 14: “Let Him Live His Life”

- The French give children as much autonomie (autonomy) as they can handle.

- The French believe kids feel confident when they can do things for themselves and do them well. After children learn to talk, adults don’t praise them for saying anything. They praise them for saying interesting things and for speaking well.

- French parents want to teach their children to verbally “defend themselves well.” Pamela quotes an informant who says, “In France, if the child has something to say, others listen to him. But the child can’t take too much time and still retain his audience; if he delays, the family finishes his sentences for him. This gets him in the habit of formulating his ideas better before he speaks. Children learn to speak quickly, and to be interesting.” Even when French kids do say interesting things—or just give the correct answer—French adults are decidedly understated in praise. They don’t act like every job well done is an occasion to say “good job.”

- This focus on the negative, rather than on trying to boost kids’—and parents’—morale with positive reinforcement, is a well-known (and often criticized) feature of French schools. What you’re taught in high school is to learn to reason. You’re not supposed to be creative. You’re supposed to be articulate.

- Pamela suspects that French parents may be right in giving less praise. After a while, children will need someone else’s approval to feel good about themselves. And if kids are assured to be praised for everything they do, they won’t need to try very hard. They’ll be praised anyway.

- New research shows that “excessive praise distorts children’s motivations; they begin doing things merely to hear the praise, losing sight of the intrinsic enjoyment.”

- Research shows that when heavily praised students attend college, they “become risk-averse and lack perceived autonomy.” These students “commonly drop out of classes rather than suffer a mediocre grade and have difficulty picking a major. They’re afraid to commit to something because they’re afraid of not succeeding.” This research also refutes conventional American wisdom that parents should cushion the blow with positive feedback when kids fail at something. A better tack is to gently delve into what went wrong, giving kids the confidence and the tools to improve.

“The Future in French”

- What has really connected Pam to France is discovering the wisdom of French parenting. She’s learned that children are capable of feats of self-reliance and mindful behaviors that, as an American parent, she might never have imagined.

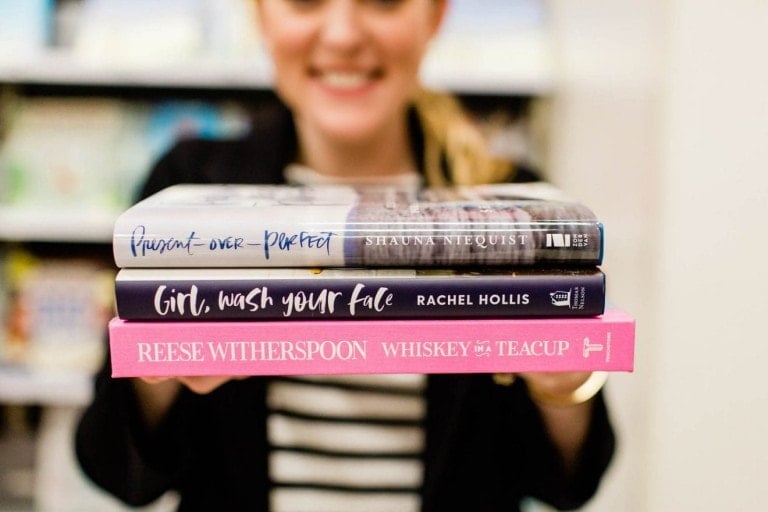

https://www.facebook.com/teambabychick/videos/1254860144562392/

We want to thank Wine Down Box for the delicious bottles of wine and treats from their subscription boxes. We loved them! It was the perfect way to “wine down” the evening and discuss an interesting book. Two thumbs up!