Low milk supply is challenging to navigate, and not just when it comes to the logistics of infant feeding. When you plan to exclusively breastfeed and discover barriers to reaching that goal, the experience can be devastating. It’s not uncommon for mothers with low milk supply to feel isolated in their experience, have difficulty finding adequate support, and feel invalidated in their struggles.

The reality is that up to 10-15% of mothers will experience low milk supply because of biological maternal barriers to exclusive breastfeeding.1 Even more, mothers will experience low milk supply due to barriers to effective feeding after birth. Low milk supply, also called lactation insufficiency, is defined as producing an amount of breast milk less than the volume required to sustain infant growth by exclusive breastfeeding.2

What causes a low milk supply?

Low supply causes can be broken down into two categories: Primary and Secondary.

Primary Low Supply

This results from any medical issues or anatomical factors in the mother contributing to a low milk supply. Primary low supply causes can include the influences of specific primary conditions, including:

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

- Thyroid Dysfunction

- Diabetes or Insulin Resistance

- Hypertension

- Luteal Phase Defect

- Previous Breast Surgery

- Postpartum Hemorrhage

- Insufficient Glandular Tissue

- Micronutrient Deficiencies

Each of these conditions can impact lactation in different ways. However, many impact hormonal health and/or the development of specific breast components necessary for lactation. These conditions don’t automatically mean a person will have a low milk supply. Instead, the unique influence of these conditions on an individual’s health dictates how they might interfere with a person’s lactation abilities.

Secondary Low Milk Supply

This results from issues arising with milk transfer and breast draining after birth, interrupting or interfering with sustaining or establishing full lactation. Examples of secondary low supply causes include:

- Delayed initiation of breastfeeding (first feeding occurring beyond one hour after birth).

- Developmental or physical conditions in the baby that affect milk transfer, including tongue-tie or other oral restrictions, premature birth, heart conditions, and intellectual disabilities.

- Infrequent or inefficient breast emptying.

- Providing supplemental feedings without draining the breasts.

Secondary low milk supply differs from primary low supply in unique ways. Unlike primary low supply, it isn’t the result of hormonal dysfunction or anatomical barriers to breastfeeding. Secondary low supply can sometimes be reversed, and milk production increased to the extent needed for exclusive breastfeeding. In contrast, that’s much less likely or not possible with primary low supply. Primary and secondary low supply can occur separately or in tandem.

How Lactation Happens

It’s important to understand the physiology of lactation when you’re struggling with low milk supply. Understanding the mechanics behind lactation will give you a better understanding of the why behind your struggle.

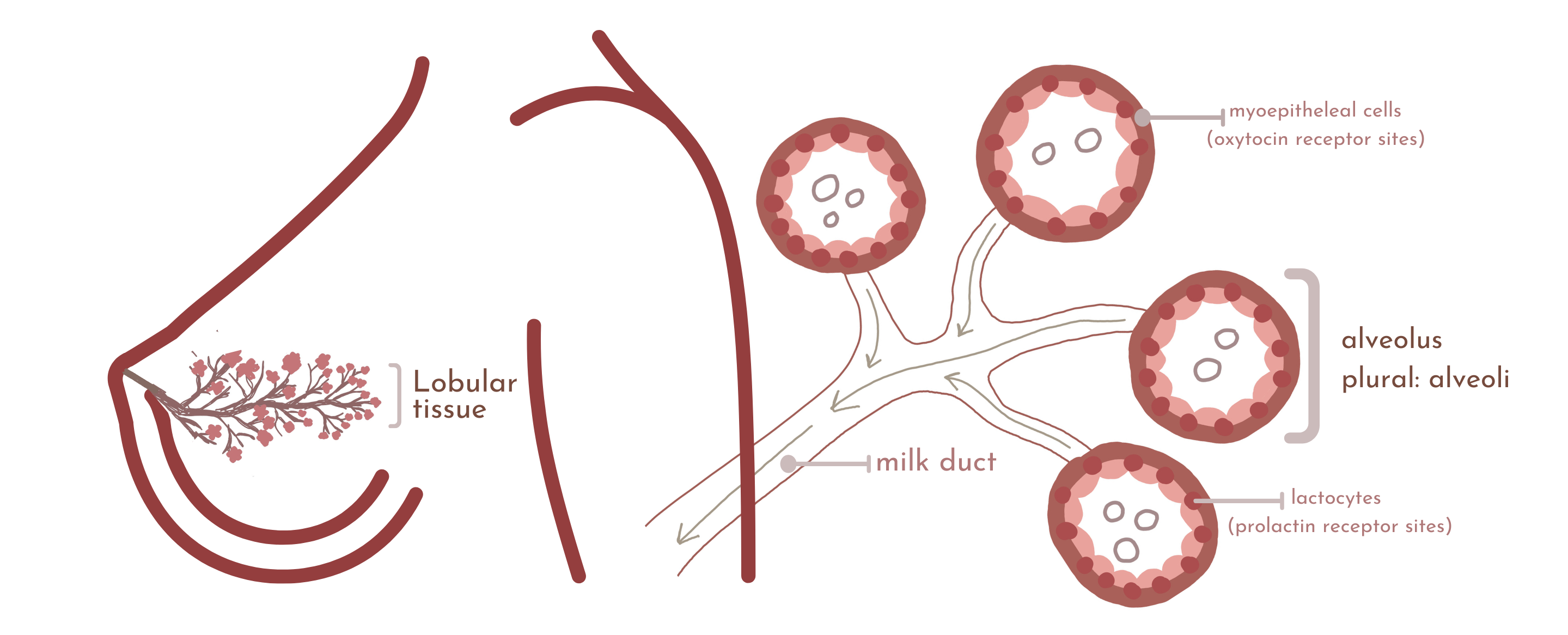

The mammary gland is a branching organ, which is why you see illustrations depicting the inside of the breasts so often as a blooming tree or flower. The breast comprises different components: primarily fat and lobular (or glandular) tissue. From birth to lactation, women’s bodies go through unique periods of growth where blossoming happens in that lobular tissue.3

Breast Development

The most influential times of breast development are early puberty, adolescence, and pregnancy. During puberty, alveoli cells develop inside the breasts and combine in clusters to make up the lobular tissue. Alveoli later become your milk-making factories that enable milk production.

During each menstrual cycle, more alveoli are laid in response to hormone actions in the body. When pregnancy arrives, these alveoli undergo an immense transformation, duplicating and transforming to create cells called lactocytes that line the alveoli. Lactocytes are produced in response to the uniquely high levels of progesterone you experience in pregnancy, mainly sourced from the placenta.

How Milk is Made

After childbirth (specifically after full delivery of your placenta), those lactocyte cells are what create milk. They’re also called prolactin receptors because the secretion of the prolactin hormone influences their action. They were created and filled with progesterone in pregnancy, which makes colostrum. Once the placenta is delivered, progesterone in the lactocytes is replaced with the hormone prolactin. This is why you have a transitional period between colostrum and white milk.

When the baby suckles, prolactin is secreted from the brain into the bloodstream, telling the lactoctyes to create milk. The milk is then pushed into the hollow part of the alveoli, where it’s stored until oxytocin tells the alveoli to release it. That release of milk and oxytocin surge happens in response to nipple stretching and the baby’s hands massaging the breasts, which becomes a conditioned reflex. The release is also known as your “let-down.”

Lactocytes are set, or primed, for milk production by nipple stimulation and breast emptying after birth. These actions help increase prolactin, which enters the lactocytes and begins churning out milk. The first three weeks after childbirth seem to be the most influential in setting these receptors, though research still hasn’t given us a definitive answer regarding that timeline.

Factors That Impact Primary and Secondary Low Supply

Primary low supply happens when these processes are interfered with or disrupted due to hormonal or anatomical conditions. These conditions can result in insufficient glandular tissue, dysfunction in the hormones necessary for these processes, or interference with the cellular communication required.

Secondary low supply is a product of insufficient or ineffective breast draining after childbirth and your body’s response to that. More specifically, it’s a product of FIL, or The Feedback Inhibitor of Lactation, a protein in breast milk. As the alveoli fill with milk, the concentration of FIL rises. When breasts are engorged or filled to capacity, FIL tells the body to stop making milk. Specifically, it blocks prolactin and slows milk synthesis. Recurrent high levels of FIL shut down prolactin receptor sites. When those sites are shut down, we lose the ability to produce as much milk. The only way to decrease FIL is to empty that milk from the breasts. This is why frequent breast emptying is necessary to sustain supply.

Treating Low Milk Supply Depends On Its Root Cause

Secondary Low Milk Supply

Additional, consistent, and efficient breast draining can increase milk production for secondary low milk supply. Decreasing high levels of FIL and stimulating prolactin levels can recover some (if not all) of those prolactin receptor sites. Boosting supply is considered relactation because you’re attempting to reset those no longer active lactocytes.

What you can do to help:

If you’re experiencing secondary low milk supply and exploring options to increase breast milk production, some great approaches are:

- Parallel pumping

- Switch nursing

- Hand-expressing intermittently throughout the day in between feeds

- Power pumping

- Incorporating more feeding sessions at the breast or pumping more frequently

Be patient.

It can take up to 5-7 days of consistent effort to see initial results. With secondary low supply, it can take up to a month to regain the lost supply. Further, an increase from consistent interventions after a month isn’t likely. Relactation can be complete (restoring lactocytes to provide enough milk for exclusive breastfeeding) or partial (providing an increase in supply below that amount). In a 2018 study on relactation for low supply, milk increase and relactation were observed in all participants. However, for mothers whose children were over six weeks old, relactation to the extent needed for exclusive breastfeeding only occurred in 30 percent.4

Check for transfer issues.

A lot of mothers have experienced secondary low supply as a result of transfer issues in baby. When a baby presents with problems in oral function, it can decrease supply, as the infant cannot efficiently drain the breasts. Assessing for transfer issues in baby can be beneficial while trying to increase supply. Working with an IBCLC can also help as you navigate all these steps.

When exploring these options, it’s important to be mindful of what’s sustainable and accessible to you, even in the short term, and prioritize your mental health. The more stimulation and breast draining, the greater the chances of increasing supply. However, approaching these interventions should always be balanced by navigating the healthiest practices for you.

Primary Low Milk Supply

Identifying and treating your root cause may help influence milk production for primary low supply. Many conditions can contribute to primary low supply, and investigating potential conditions usually involves bloodwork. Labs drawn to evaluate your prolactin, thyroid, and glucose health can be a good first step as you explore conditions that may be causing low milk supply. Knowing the why behind what’s happening can inform what treatments may be beneficial and provide a reason behind what you’re experiencing.

It’s important to remember that several primary conditions impacting milk supply don’t just impact the process of how milk is made right now but how your breast anatomy developed before childbirth, which lays the groundwork for lactation. Finding an IBCLC who has additional training in primary low supply can help as you navigate identifying your root cause.

Many mothers who experience primary low supply are told to triple feed, keep trying, and that the milk will come. When that doesn’t happen, it can be incredibly heartbreaking to discover your body’s limitations. For some of us, no amount of pumping, drugs, or supplements can increase our milk production. It isn’t always a matter of effort. Sometimes, it’s your biology.

Don’t blame yourself; it may be out of your control.

With low supply, moving beyond our limitations means restoring a sense of autonomy that’s been lost. When we decide to feed one way, and that choice is taken from us, we can experience overwhelming grief. There’s a stigma we face in finding our way. Sometimes, there’s judgment in how we choose (or need) to feed our children. Restoring a sense of control in a situation you feel so outside of control means understanding your options and making choices according to what you can influence.

You can combo feed using formula or donor milk. You can explore what modes of supplementing you want to use. Maybe you buy an at-breast supplementer. Or perhaps you comfort nurse or pump for an evening bottle. Possibly, your mental health is impacted negatively by continuing to breastfeed. Maybe you just need some time to allow your grief to breathe until you decide which way to go.

Breastfeeding isn’t just about supply and demand. There’s a lot of other factors that go into it. If you’re struggling with low supply, please know you’re not alone.